Model Checking: Essential Logic and Automata Theory You Need to Know

In today’s interconnected world, the reliability and safety of software and hardware systems are paramount. From autonomous vehicles to medical devices and critical infrastructure, a single flaw can have catastrophic consequences. This is where Model Checking comes in: a powerful set of techniques designed to systematically verify the correctness of systems, ensuring they behave exactly as intended, every single time.

This blog post marks the beginning of our comprehensive series on Model Checking. We’ll embark on a journey from foundational concepts to practical applications, equipping you with the knowledge to understand and implement these vital verification methods. In this post, we’ll lay the groundwork by exploring the core theoretical pillars that underpin model checking: the principles of logic, formal verification and automata theory. Get ready to master how we can build truly robust and hazard-free systems!

1. Logic

Logic is the field of mathematics responsible for studying Boolean expressions, i.e., expressions which can either be true or false. Simple examples are “the weather is hot” and “I love you”. Although studying those sorts of phrases is not optimal for mathematicians, logic is still one of the core branches and is very widely used in different engineering fields, especially electrical and computer engineering, but also in computer science.

One differs mainly between propositional logic, which consists of the known Boolean operators (especially AND, OR and NOT) and of Boolean variables called propositions. An example of a propositional logical formula is:

\[ (p \text{ OR } (\text{NOT } q)) \text{ AND } p. \]

The second important type of logic is predicate logic. This is widely seen as the general version of propositional logic, where the variables are not necessarily Booleans, but can be of any sort. In addition, we have, other than the Boolean operands, the quantifiers \( \forall \) (forall) and \( \exists\) (there exists). Lemmas and axioms in mathematics are mostly written in predicate logic. For example, we can define a sort called Group, a constant \( e \) of the sort Group, an operation \(*\), and then use the Group Axioms to define the relations between elements of the Group:

- \( \forall x. \exists y. \space \space x * y = e \)

- \( \forall x. \forall y. \forall z. \space \space x * (y * z) = (x * y) * z \)

- \(\forall x. \space \space x * e = x \)

2. Formal Verification

Given a formula in propositional logic, it is generally easy to prove or disprove its validity using a set of rules.

For predicate logic, this gets harder as one has to define a set of axioms, which in many cases can contradict each other, leading to all the rules to be false. For axioms that do not contradict each other (called consistent), one can prove, with enough knowledge, if a formula is true.

One can extrapolate the formal verification to programs, where one can study a program’s properties and its states. This includes the values of some of its variables, the termination of the program and the correctness of a returned value. This enriches the propositional logic by other operands, such as the diamond operator \(\langle.\rangle\), which tells for a program \(p\) and a formula \(\phi\):

\[ \langle p \rangle \phi \text{ is true}\] \[\text{ if and only if} \] \[ p \text{ always terminates and } \phi \text{ holds after the program } p \text{ terminates} \]

3. Model Checking

Model Checking is the study of a modeled system for correctness and safety constraints. In many safety-critical systems (aircrafts, robots, railway crossings…), modeling the system and proving its safety criteria always hold is a critical step, because:

-

- Testing the system itself instead of a model has extremely high costs. Imagine having to test a railway crossing by driving a train and cars in different situations, each with the possibility to lead to a collision.

- Testing the system a few (or even many) times cannot be considered safe, as long as there is no warranty that the model cannot lead to an issue in a rare case that only appears under very specific conditions (especially if there are parallel tasks involved).

This is why the main role of model checking is ensuring a hazard-free system in all possible cases.

For this, model checking defines two other types of logic to define the changes happening inside a model at different steps. As computers only handle discrete values and structures and cannot work with continuous values (like real numbers), model checking runs on discretized times. The two logics are called Linear Time Logic and Computation Tree Logic and will be discussed in detail in the next blogs of this model checking series.

4. Automata and Languages

In computer science, we define an alphabet as a finite set of characters, a word as a string composed of these characters, and a language as a set of such words.

For example:

- \(A = \{a, b\}\) is an alphabet.

- “aab”, “bb”, “a” and the empty word “” are all words over \(A\).

- \(L = \{“aab”, “bba”, “a”, “”\}\) and \(L’ = \{w \mid w \text{ word over } A \text{ that starts with an } a\}\) are languages over \(A\).

Deterministic Finite Automata (DFAs)

One of the main cores of theoretical computer science are automata, which can be used in various use cases, including pattern matching (this is the case with regular expressions, for example, where we only want to validate strings having a special form), compiler building (where we want to build a syntax tree from a given code to generate its machine code version) as well as model checking. For the sake of simplicity, we define in this blog Deterministic Finite Automata (DFAs) only. These are directed graphs, where the nodes are called states and the edges are called transitions. Each transition is annotated with a letter, and some of the states are marked and in that case they are called final (or accepting) states. Each DFA also has a unique initial state, which is marked by an ingoing transition.

A DFA can accept or reject a word by reading it letter by letter, and following its path on the directed graph. If we land after reading all the letters on an accepting state, then we accept the word, otherwise, we reject it.

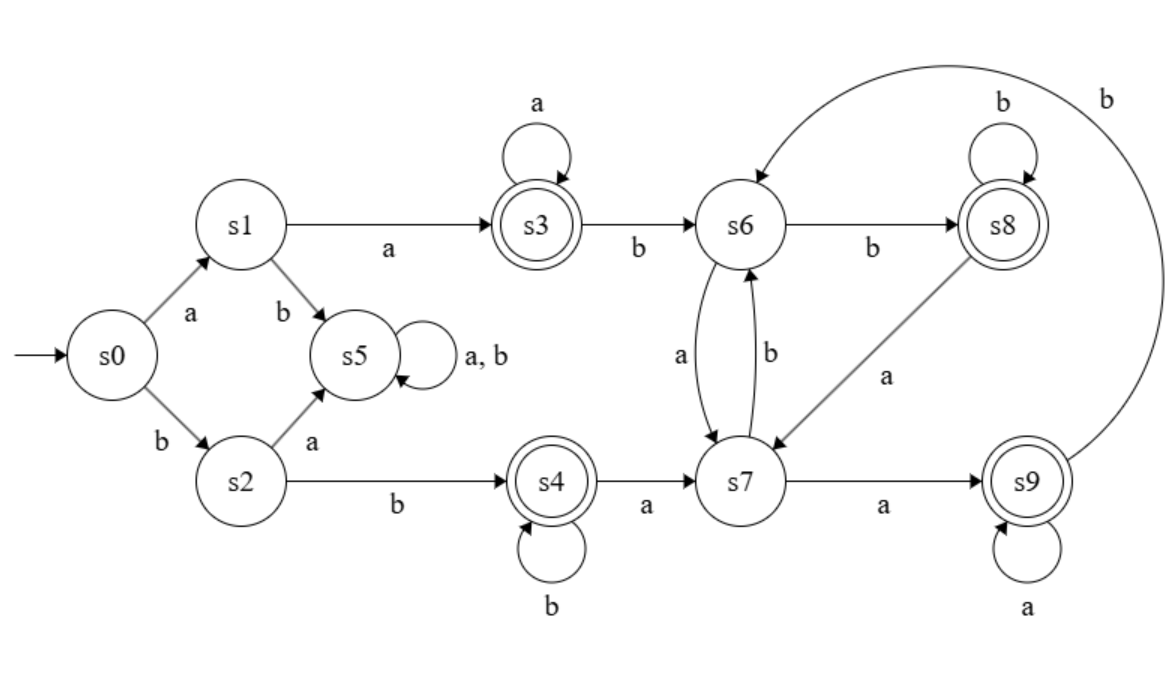

For instance, given the following DFA:

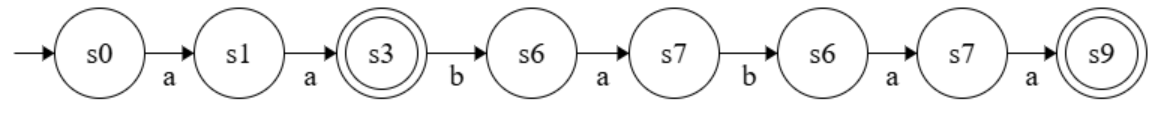

It accepts the word “aababaa” because we land on the accepting state s9 after reading the word:

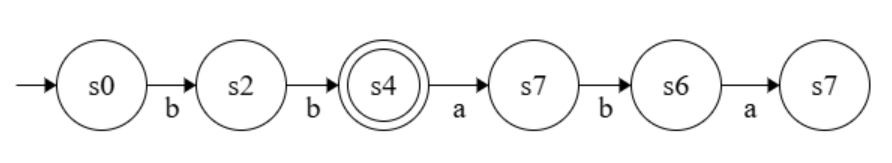

However, it does not accept “bbaba” because we land on the non-accepting state s7 after reading the word:

From that, we can see that every DFA accepts only some set of words, a.k.a. accepts some language. For the previous example, the DFA accepts the language of words starting with a doubled letter and ending with a doubled letter.

5. Programming

Each blog of this series will contain a coding part to practice what we have learned. Try to code yourself to get used to the context and take a look at our solution for reference if you are stuck. For simplicity, we will be using Python as our programming language. Yet, the concepts can be applied to any programming language of your choice.

This blog’s coding challenge:

-

-

- Implement a class State to simulate a DFA state (node of the directed graph) with the following properties:

- Each state has a name and can be an accepting state.

- Each state has maps to each letter of some alphabet another state.

- You can read a letter from a state, and it will return the next state.

- Implement a class DFA to simulate a DFA such that:

- A DFA has an alphabet and an initial state.

- One can check if the current DFA is valid. This is the case if, for every letter of the alphabet, every state has exactly one outgoing transition with that letter.

- One can check if a word is accepted by the DFA or not.

- One can check if a DFA accepts at least one word, i.e., if there is a path from the initial state to some accepting state.

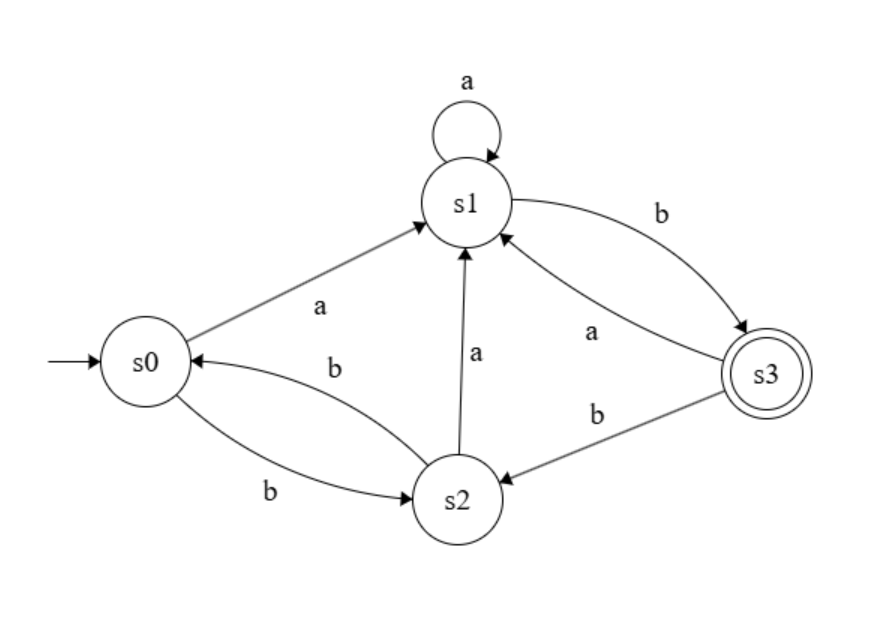

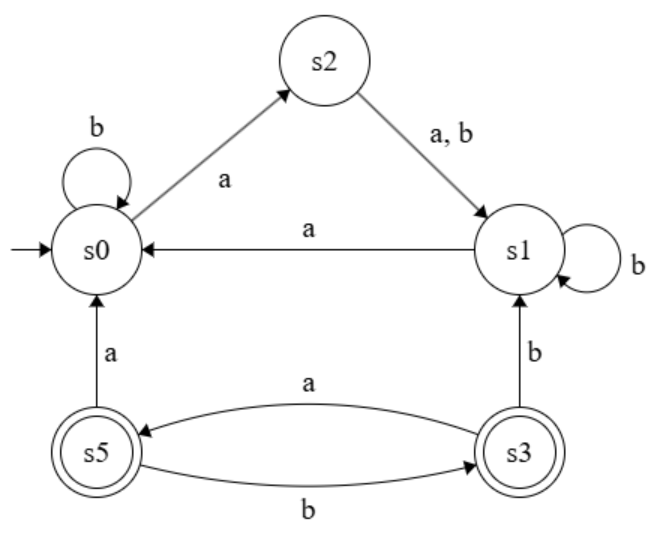

- Check if the following DFAs accept “ab”, “baaabababab” and “”. Check which of the DFAs accepts no word.

- DFA 1:

- DFA 2:

- DFA 1:

Solution:

class State: def __init__(self, name: str, accepting: bool = False) -> None: self.name = name self.is_accepting = accepting self.next_states = {} def add_next_state(self, letter: chr, state: "State") -> None: self.next_states[letter] = state def read_letter(self, letter: chr) -> "State": if letter not in self.next_states: raise KeyError(f"Can't find next state for the letter {letter}") return self.next_states[letter]class DFA: def __init__(self, initial_state: State, alphabet: set[chr]): self.alphabet = alphabet self.initial_state = initial_state def is_valid(self) -> bool: visited = set() # The names of the already visited states ones_to_visit = [self.initial_state] # The states that are not visited yet while ones_to_visit: # While there is still a state to visit current_state = ones_to_visit.pop() # Take the state to visit visited.add(current_state.name) # Mark that state as visited current_letters = set() # The letters that this state has a mapping for for letter, next_state in current_state.next_states.items(): # For each next state current_letters.add(letter) # Add the letter to the letter set # If the next state is not visited, mark as a state that needs to be visited as well if next_state.name not in visited: ones_to_visit.append(next_state) # The mapping of the state must be exactly the same as the alphabet of the DFA if current_letters != self.alphabet: return False return True def accepts(self, word: str) -> bool: if not self.is_valid(): # We exclude non-valid DFAs return False current_state = self.initial_state # Start at the initial state # Read letter by letter for letter in word: # If the word encounters some letter not in the alphabet, then we automatically reject if letter not in self.alphabet: return False current_state = current_state.next_states[letter] # Go to the next state return current_state.is_accepting def is_empty(self) -> bool: visited = set() # The names of the already visited states ones_to_visit = [self.initial_state] # The states that are not visited yet while ones_to_visit: # While there is still a state to visit current_state = ones_to_visit.pop() # Take the state to visit # If our visited state is accepting, we are done if current_state.is_accepting: return False visited.add(current_state.name) # Mark that state as visited # Add all next states which are not already visited for next_state in current_state.next_states.values(): if next_state.name not in visited: ones_to_visit.append(next_state) return TrueDFA 1 accepts “ab” and “baaabababab” but not the empty word. It does not accept an empty language because it accepts some words (ab for example).

s0 = State('s0') s1 = State('s1') s2 = State('s2') s3 = State('s3', True) s0.add_next_state('a', s1) s0.add_next_state('b', s2) s1.add_next_state('a', s1) s1.add_next_state('b', s3) s2.add_next_state('a', s1) s2.add_next_state('b', s0) s3.add_next_state('a', s1) s3.add_next_state('b', s2) alphabet = {'a', 'b'} dfa = DFA(s0, alphabet) print(dfa.is_valid()) # Prints "True" print(dfa.is_empty()) # Prints "False" print(dfa.accepts('ab')) # Prints "True" print(dfa.accepts('baaabababab')) # Prints "True" print(dfa.accepts('')) # Prints "False"DFA 2 does not accept neither “ab” nor “baaabababab” nor the empty word. It accept the empty language because it accepts no word at all.

s0 = State('s0') s1 = State('s1') s2 = State('s2') s3 = State('s3', True) s5 = State('s5', True) s0.add_next_state('a', s2) s0.add_next_state('b', s0) s1.add_next_state('a', s0) s1.add_next_state('b', s1) s2.add_next_state('a', s1) s2.add_next_state('b', s1) s3.add_next_state('a', s5) s3.add_next_state('b', s1) s5.add_next_state('a', s0) s5.add_next_state('b', s3) alphabet = {'a', 'b'} dfa = DFA(s0, alphabet) print(dfa.is_valid()) # Prints "True" print(dfa.is_empty()) # Prints "True" print(dfa.accepts('ab')) # Prints "False" print(dfa.accepts('baaabababab')) # Prints "False" print(dfa.accepts('')) # Prints "False" - Implement a class State to simulate a DFA state (node of the directed graph) with the following properties:

-

6. Further Reading and References

- Clarke, E.M., Grumberg, O., & Peled, D. (1999). Model Checking. The MIT Press.

- Huth, M., & Ryan, M. (2004). Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and Reasoning about Systems (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Hopcroft, J.E., Motwani, R., & Ullman, J.D. (2006). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Automata made using: https://madebyevan.com/fsm/

Popular Posts

-

Probabilistic Generative Models Overview

Probabilistic Generative Models Overview -

Gaussian Mixture Models Explained

Gaussian Mixture Models Explained -

Living in Germany as Engineering Student : Why is it hard living in Germany without speaking German?

Living in Germany as Engineering Student : Why is it hard living in Germany without speaking German? -

Top 7 AI writing tools for Engineering Students

Top 7 AI writing tools for Engineering Students -

Top AI Posting Tools Every Engineering Student Should Use to Be Innovative Without Design Skills

Top AI Posting Tools Every Engineering Student Should Use to Be Innovative Without Design Skills